Charles H. Cook, A Citizen Soldier in the Air by Bruce Irving

Interview, research and article by Flying Singer.

Flying SingerCharles H. Cook flew a B-24D named "Cookie" with the 90th Bombardment Group in the southwest Pacific in 1942-1943. At that time, Allied forces were greatly outnumbered, and Japanese invasion of New Guinea and Australia was a very real threat.

Bruce Irving has interviewed Charlie Cook and composed this valuable record of his aviation career.

A Citizen Soldier in the Air by Bruce Irving (pdf) >> Click to download

2000 - Charles H. Cook stands next to a B-24 Liberator some 50 years after he risked his life flying just such an aircraft in defense of Australia in the South Pacific.

Charles H. Cook passed away on on Saturday January 20th, 2007. He is missed by his friends and family.

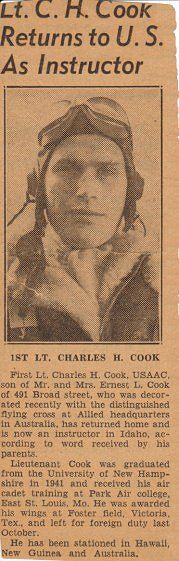

DFC: the Distinguished Flying Cross

Introduction

Charles H. Cook is my father-in-law. As I have gotten to know him over the last couple of years, I have enjoyed hearing his occasional stories of his experiences as a B-24 pilot in the Pacific in WWII.

He was always very modest about these stories, but I wanted to know more, about how he got interested in flying, what it was like to fly in combat, and all the rest. So I asked if I could interview him, and he agreed.

Charles H. Cook ca. 1942

At the age of 80, Charlie's memory of events of almost 60 years ago is amazing to me. We talked for about three hours on August 6, 2000 at Charlie's home in Keene, New Hampshire.

Most of this article is based on Charlie's recollections and items that he saved, but I also want to thank Jason Dilworth for helping with the background research and for providing scans of photographs in his collection. Jason's late grandfather, George C. Porter, was a gunner on another B-24 ("Big Chief") in Charlie's squadron in New Guinea, the 321st Bomb Squadron, 90th Bomb Group.

Other credits, references and links are at the end of the article. From flight records kept by Charlie and with help from Jason Dilworth and Wiley Woods, I was able to find the names of all nine of Charlie's crew members. I have attempted to contact these men, without much luck so far. If a reader knows any of the crewmen mentioned in this article, please contact me.

Charlie cared a lot for that crew, and they were a great team, so we'd love to hear from or hear about any of them. Thanks a lot!

Barnstormers

When Charlie Cook was a boy of ten in 1930, he went to see some barnstormers who had come to his home town of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

They did some amazing things, he says 70 years later, smiling at the memory, "like picking up a handkerchief with a wing tip, or flying inverted just above the grass. They flew biplanes, maybe Curtis Jenny's, and they would do anything with those airplanes.". After the shows, they would sell rides.

They'd take you up and show you around the town. My older brother was working, so he paid the $5 for me and I went for a flight. They even did aerobatics on that ride, loops and stuff. It was fun, and I was hooked!

The Curtis JN-4 Jenny was a WW1-era biplane flown by many barnstormers.

Civilian Training (Taylorcraft)

Charlie didn't get a chance to fly again for about 11 years, when he was studying psychology in college.

In spring of 1941 I was a senior at the University of New Hampshire, and some of my buddies and I heard about the Army's Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP). We decided to give it a try.

In 1941, the U.S. was not yet at war, but it seemed to be coming, and programs were in place to start training more pilots. The Army paid for the lessons, which were given by civilian flying schools in regular civilian trainers.

All we had to pay was $10 for a flight surgeon's physical exam - the Army paid the rest. The Army also set the very rigid curriculum, in a combination syllabus and log book that Charlie still has. It shows that he took his first flight on March 1, 1941, and soloed March 28, after just 9 flying hours.

Excerpt from Charles H. Cook's flying log on March 28th 1941

"It was a little Taylorcraft, a tail dragger. The flight school was nothing more than a farmer's field - it sure wasn't flat."

The Taylor Cub

Winter flying presented additional challenges. "We'd put skis on the wheels, but to take off, you'd have to rock the wings left and right to keep the skis from sticking to the snow." After the specified forty hours, plus a number of ground school classes taught by UNH professors, Charlie took his test flight and received his private pilot's license on June 3, 1941.

Primary Training (PT-19)

The Army was naturally screening for military pilots in this program. " At the end they said, "You liked that didn't you? How about some more?" We said "Sure!" So Charlie signed up to enter Army Flight Training.

He took the oath and was shipped out to Parks Air College in East St. Louis, Illinois on September 27, 1941. This was a civilian school providing Primary Flight Training under contract to the Army. The instructors were civilians, but the planes were Army, Fairchild PT-19 "Cornells" - a single-wing primary trainer.

The Fairchild PT-19 Cornell was the primary trainer Charlie flew in 1941.

"The PT-19 was a nice little airplane. It was a little under-powered, but it was fully aerobatic, it would do any maneuver you wanted, though you might have to dive a little to build up some airspeed to do a loop or an Immelman. It was fun to fly." Charlie recalls, "I was on solo flight in maybe 8 hours, and I loved to do inside loops, outside loops, all kinds of aerobatics."

Landings were not a big deal, "but one day I was coming in pretty high, so I had to slip the airplane - really turn the side of the plane into the wind. I heard a funny sound, and when I landed, I found that a big section of fabric had been blown off the side of the fuselage!"

PT-19's at Parks Air College, 1941 (Charlie photo).

Primary lasted about three months, from October through December 1941. "I was in Primary when we heard about Pearl Harbor, and what a blow that was - when they announced it, it got so quiet, you could hear a pin drop - so we knew we were in it - not sure where, but we knew it would be war."

He did well in his training, until he got to the final test flight (what we call a check ride these days). "The test pilot was a real S.O.B. He watched me do the preflight, then told me to take off. Once we got to the test area, he would tell me to do a specific maneuver, but as soon as I would start, he would grab the stick from the back seat and give my knees a hell of a beating. I was a good pilot, but he completely messed me up, and I came back from that flight in tears." When he landed, his instructor, Mr. Small, was waiting. "Cook, what happened up there - you failed that flight test - I know you're better than that!"

Charlie told him what the examiner had done, and Small said, "Let me talk to him." The next day, he flew a second test flight, and the examiner didn't touch the controls or say a word other than the maneuver he wanted to see. This time his instructor had good news, "You passed, Cook, with the highest grade he ever gave a student: C!"

It was good enough to go on to basic training.

Basic Training (BT-15)

Basic training was at an Army base in San Angelo, Texas, "out in mesquite country," Charlie says. "We flew the BT-15, which was the lousiest airplane I ever flew. It was under-powered and couldn't do much of anything, not even aerobatics" (students nicknamed this plane the vibrator because they shook like mad when you tried to pull them out of a spin).

The Vultee BT-15 Valiant basic trainer, 1942

I asked if they worked on formation flight there, and Charlie said no, he never got formal formation training until he got to bombers (though this photo suggests they were at least doing some informal formation flight at this stage!).

"We did some cross country flights, improved our navigation, but basic training really wasn't much."

They did have a little fun on the ground, though. "We organized a barbershop quartet, and we would put on a little entertainment at the base - I was first tenor." They also got some flight simulator time in Basic, but not like the flight sims we have today. They practiced "needle, ball, and airspeed" instrument flying in Link C-3 Trainers.

The Link 'Blue Box' was used for instrument flight training.

This was a full motion simulator driven by compressed air, but there were no visuals at all, just a cockpit with instruments and controls and an opaque hood. Instrument flying would prove to be very important when Charlie flew combat in the stormy skies of New Guinea. Charlie again did well in his flying and went on from Basic to Advanced Training in the AT-6 Texan.

Advanced Training

"Now the AT-6 was a hell of a nice airplane - extremely quick and easy to fly, as close as you could get in a trainer to an actual fighter plane."

AT-6 Texan trainers in formation.

This training was at Fosters Field in Victoria, Texas, right on the Gulf Coast. "There were some islands off shore where we did gunnery practice, air to ground, strafing." They also practiced air-to-air gunnery in the AT-6, shooting at a fabric target towed on a long cable by a pilot who everyone agreed had to be crazy.

Was that part fun?

"It was all right, until you'd get back down and not find any holes in your target!"

Dog fighting was the most fun. "We called it rat-racing, and it was great. We'd play follow the leader, twisting and turning until someone fell out of line. We'd zoom around the beautiful cumulus clouds, aiming for a little gap which might close up, then you'd be flying blind on instruments for a little bit."

Charlie even took pictures on some of these flights!

As you might expect, they also pulled off a few "crazy stunts."

Charlie suited up and ready for a flight in the AT-6 Texan Advanced Trainer

Charlie recalls, "I flew the AT-6 under a bridge one time - they yelled at me, said never to do that again, but it wasn't a big deal - they needed pilots badly, so they weren't going to wash you out for something like that."

A 'rat-racing' tail-chase in the AT-6 (Charlie photo, 1942).

Charlie completed his advanced training and received his wings and commission as a second lieutenant on April 29, 1942.

Meeting the Big Boys (B-17, B-24)

After advanced training, pilots were assigned to an operational airplane, and Charlie was sent to fly heavy bombers in Sebring, Florida. "That's where I met the big boys. At first I was checked out in the B-17, which was a dream airplane, big but responsive and as easy to fly as the Texan. You could fly that thing with your little finger."

The instructors were good, "they just made us fly the airplane," Charlie recalls. "You'd have to pass a blindfold test, knowing where every little thing was located, but even so, we would always use checklists. Whether you were a one year or a twenty year pilot, you never trust procedures to memory when you can use a checklist."

The B-17 was easy to taxi, didn't want to ground loop, and handled well in the air. "Even if they cut your engines, it would glide well. It had lot of wing and huge control surfaces". They did a lot of high altitude flying, including stalls and spins."

Intentional spins?!?

Oh sure, they'd make you pull the nose way up and it would wobble and shimmy and it would want to drop a wing.

You'd hold it off as long as you could then do a two, two and a half turn spins, then recover just like in a PT-19.

B-17 transition took about four months (May-August 1942) and included a number of long cross-country flights and temporary base assignments. "After I had been checked out in the B-17, I assumed I'd be going to Europe, but then I got orders to report for B-24 training, and I was told I'd be going to the Pacific".

B-17 pilot's view (1942 Charlie photo, in formation over Grand Canyon, Arizona - picture by Charles H. Cook, 1942.

The four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress was a 'dream airplane' to fly, according to Charlie.

So at Alamogordo, New Mexico in August 1942, Charlie started training in the Consolidated B-24D Liberator, which had only recently entered service.

B-24 Liberator production line

Of more than 18,000 Liberators produced in the war years, only a few remain today, and only one flyable example exists, the B-24J "Dragon and His Tail" operated by the Collings Foundation .

Of more than 18,000 Liberators produced in the war years, only a few remain today, and only one flyable example exists, the B-24J "Dragon and His Tail" operated by the Collings Foundation .

This transition was quicker than the AT-6 to B-17 (about two months). What was it like to fly? "Not as nice as the B-17. For example, the B-17 had an auto-pilot that really worked well. It would hold your heading and altitude real nice. The B-24 on auto-pilot was all over the place. You wouldn't have to wrestle the yoke as much, but you'd constantly be adjusting the auto-pilot settings."

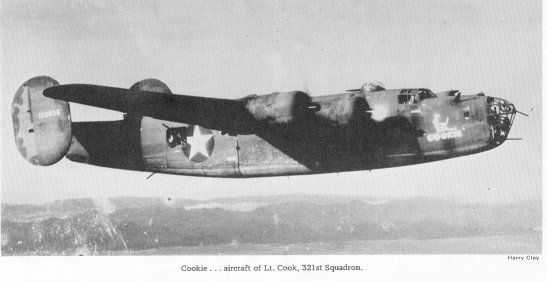

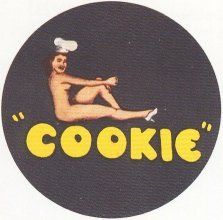

In Alamogordo, he was assigned "his" B-24D (serial number 41-23839), which he would eventually name "Cookie" (pilots at the time got to name one aircraft, though in combat, they didn't always fly that plane).

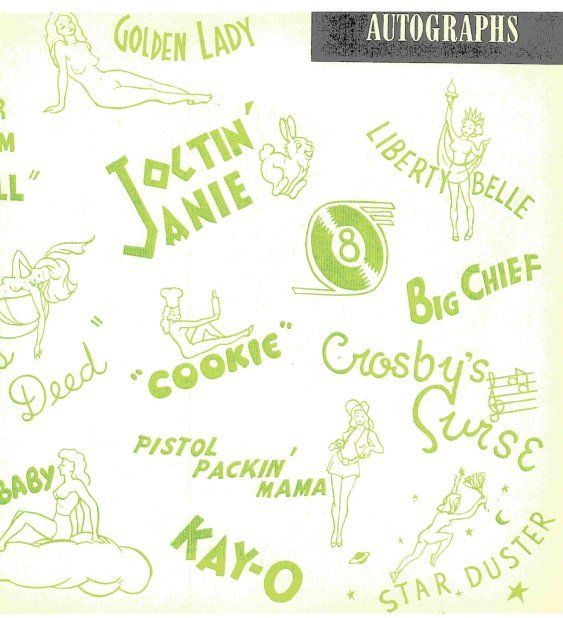

B-24 Side Art from "Bombs Away"

Despite all this, Charlie recalls that the D-model B-24 was not a bad airplane to fly. "Later models got heavier and more sluggish, even with the upgraded 1200 HP Pratt and Whitney engines. They had four gun turrets, which created a LOT of drag. They also put in huge armor plates behind the pilot and co-pilot, though I'm not sure who they were supposed to protect you from, your radio operator and navigator?"

A lot of pilots refused to fly with this extra weight, since there was only Plexiglas in front and above them anyway. "Many guys got shot from the front, above, or below - I heard of one guy who got a Purple Heart for a burned ass - the bullet got spent in the seat cushion - that's what you call a hot seat!"

Travels with Charlie

Once checked out in the B-24, Charlie began to fly to a number of different bases in the U.S. First he flew up to Topeka, Kansas.

This is where he was assigned the crew of nine men he would fly with for most of the next year

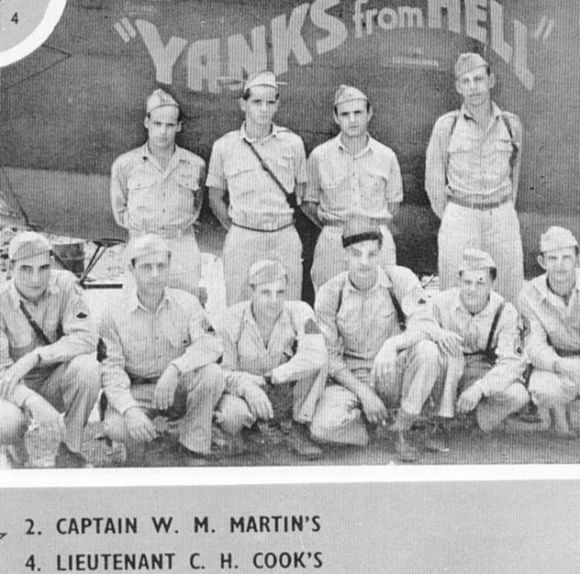

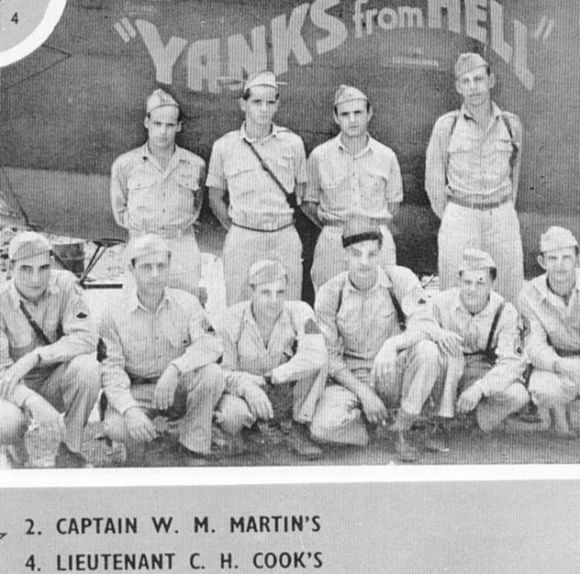

Charlie (back left) and crew (unknown why they were not posed here with Cookie).

- Co-pilot Nathan T. Bradford

- Navigator Morris H. Schafer

- Bombardier Andrew F. Fedyk

- Radio operator Marvin Henslovitz

- Flight engineer Shelby Smith

- Gunners Raymond Perzesker, William H. Thomas, Gerald A. Zimmerman, and Ercel Londrie).

There was a bomb range nearby, and they started practicing with live ordnance. This was followed by long flights to bases in Idaho, New Mexico, Long Beach, and finally San Francisco. Advanced training prepared the crew for long-range navigation and to work as a tightly coordinated unit for the combat that was soon to come.

B-24 Liberator Cookie in flight. (thanks to John Alcorn and Jason Dilworth).

Considering that so much of their flying was to be long stretches over the Pacific Ocean, Charlie felt he was lucky to have gotten one of the best navigators in his crew. Navigation in the Pacific was a real challenge at the time, as there were virtually no navigational aids, and what charts they had were often wildly inaccurate in even the positions and shapes of the islands!

Ditching the B-24

I noted that there weren't too many landing spots out there, and Charlie said, "sure there were, they were just pretty wet, that's all!".

I asked him if they were trained on how to ditch.

Yes, and the B-24 ditches very nicely, like a big, round rock, straight to the bottom.

I thought he was joking, but when I looked into this, it seems that the B-24's bomb bay doors were rather flimsy and would collapse on impact with the water, allowing the plane to fill rapidly with water - so you didn't ditch a B-24 if you could avoid it! And did they wear life jackets for flights over water? Charlie doesn't recall having them - at least they never wore them!

Details of the front nacelles.

On October 19, 1942, Charlie and his crew took off from San Francisco in the still-unnamed "Cookie" as one of thirteen Liberators bound for Hawaii, a 14 hour flight.

One of our planes never made it there - we never found out what happened to them.

Once they reached Hickam Field, they flew their first combat missions, which were long-range patrols looking for enemy ships.

Not much happened on those flights, Charlie recalls. They also did even more training, practicing takeoffs and landings from short jungle and beach-side airfields, including air strips made from metal panels quickly laid down by combat engineers.

At one of these bases, Charlie recalls swimming in the beautiful clear Hawaiian waters with hundreds of small "octopussies". They also got to see the devastation caused by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor just eleven months earlier, and they were ready to go to war.

Cookie's side art. Name and art were applied after arrival in New Guinea.

In November 1942, Charlie and his crew departed for Australia, island-hopping to the southwest to avoid Japanese-held areas. After passing through a huge thunderstorm over the Great Barrier Reef, they arrived in Brisbane, Australia. They were only there a short time before they were sent up the coast to an air base on the York Peninsula called Iron Range.

Not jolly yet!

At Iron Range, Charlie and crew joined their squadron, the 321st Bomb Squadron, part of the 90th Bomb Group, which in turn was part of the Fifth Air Force. It's important to note that while the 90th Bomb Group later became well known under the nickname "Jolly Rogers", .... It did not have this name during the time that Charlie served in Australia and New Guinea (November 1942 to June 1943).

Colonel Rogers became the C.O. of the 90th in July 1943, and at that point, the name "Jolly Rogers" seems to have been adopted, along with the skull and crossed-bombs tail art that became quite famous. In late 1942 and early 1943, the 90th BG was part of a very small air force that served as an important stop-gap to Japanese plans to capture all of New Guinea and eventually Australia.

Insignia of the Fifth Air Force, courtesy of heavybombers.com.

Although there were some carrier-based US Navy and US Marine forces, as well as RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) planes, the Fifth Air Force had to provide most of the air power to contain the Japanese. With limited forces available, the strategy consisted of searching for and attacking Japanese shipping wherever they could, as well as attacking any Japanese bases that were within range of Allied aircraft.

Charlie was proud to be part of the 90th Bomb Group whatever they may have been called, but he likes to point out that a lot of the actions (including the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943) took place before the "Jolly Rogers" name was applied.

Night attack on Rabaul

While based at Iron Range, the 321st flew some night missions against the large Japanese naval and air base at Rabaul, on the northeast tip of New Britain (New Guinea). Charlie recalls his very first mission from Iron Range, just a day or so after arriving there.

It was a night strike on Rabaul, with five or six B-24's, led by their squadron C.O., Col. Faulkner. They were only allowed to use very faint wing-tip lights for night formation flying, which generally was not a problem - until you passed through a cloud.

"You would lose those lights in a cloud, so you'd be flying blind, hoping the other guys would all hold a steady course! It all worked out though, and I don't recall any formation accidents."

Rabaul harbour from the Air

But before they could form up, they all had to get off the ground - and that mission got off to a bad start. The very first B-24 to take off (not the C.O.'s) veered off the runway on its takeoff run, crashed in the jungle and caught fire. The fire detonated the bombs, and all of the crew were killed. Charlie recalls that Col. Faulkner told the remaining pilots that they didn't have to fly the mission that night - any one could back out, with no penalty.

"We all went anyway, but it was damn nerve-wracking to see one of your buddy crews get blown up like that." There was a lot of flak over the target, but they all returned safely to base. Quite a warm welcome to the Southwest Pacific!

Flight School for the Crew

Many of Charlie's early missions were long-range patrols, searching for enemy ships, with bombs on board to attack any that were found, which didn't happen that often. So these flights were often long and uneventful, six or eight hours of flying over the water. It was at this point that Charlie decided to break a regulation in the cause of crew safety.

Charlie (back left) and crew (unknown why they were not posed here with Cookie).

He started teaching his crew members to pilot the B-24! He would sit in the co-pilot seat and have the crew member sit in his seat and practice level flight, turns, climbs, and descents, and he would go over procedures for landing and emergencies. "I figured that if my co-pilot and I were killed or injured, but the plane was still flyable, why not give the crew a chance to make it home alive?" He doesn't recall discussing this very much with other pilots or with his C.O., so he doesn't know how many other pilots did this. But his crew seemed to like the idea, and some of them really enjoyed taking the controls.

This little flight school on patrol would soon prove to be a smart idea!

New Guinea daze

At some point, perhaps January 1943, the 321st was transferred to an air base at Port Moresby, on the southeast tip of Papua, New Guinea. New Guinea is divided by the Owen Stanley Mountain Range, and the Japanese held the northern side of the island, while the Allies held the south side. It was just a few minutes flying time between Port Moresby and the Japanese bases (Wewak, Madang, and others), but the mountains provided some protection (they were around 15,000 feet tall with some passes as low as 6,000 feet). The mountains also presented a challenge to navigation, especially in the late afternoon when powerful thunderstorms would sit astride the mountains.

Charlie recalls one particularly frightening mission when they were attempting to fly through a 6,000 foot pass between much higher mountains, on the way to a "nuisance raid" on Rabaul (they often flew all-night nuisance raids, with a string of single B-24's dropping bombs every thirty minutes). Cloud cover was complete, so they were flying totally on instruments.

They flew for the pass at 15,000 feet, figuring this would give them plenty of margin, and maybe allow them to break through on top, but this was "the worst goddamn thunderstorm I ever saw", recalls Charlie.

The violence of that storm was awful, and the turbulence was so bad, I thought the airplane would come apart. There were also ice pellets, as noisy as hell, and St. Elmo's fire (static electricity discharges) dancing all over the ship. The navigator was yelling at me, and I tried to hold course as best I could, but I could barely keep it in the air - it was the worst battering we ever had.

This sounds like a nightmare already - but it gets worse!

B-24 Cookie in New Guinea courtesy of b24bestweb.com

The engineer was already helping with the instruments, which were jumping all over the place, when something knocked out their gyro instruments (sounds like a vacuum system failure, though the gyros may have just tumbled from all the bouncing around). So now they are Back to needle-ball-airspeed, the most basic instruments, without even an artificial horizon or gyro compass.

The pitot tube was also fouled with ice for a while, so even the airspeed was suspect.

We had fun there for a while, Charlie says. "We lost a lot of altitude and I was scared to death we would run into a mountain, but there wasn't a damn thing I could do about it - I wasn't going to change course, but the compass was jumping all over the place, so I just had to try to bracket it - same with the airspeed.

We lost 7000-8000 feet in maybe half an hour, flying around 7000 feet in what we hoped was that 6000 foot pass - finally we broke through on the other side of the mountains."

They bombed Rabaul, and by the time they flew back, the evening storms had subsided, and they returned home safely.

New Guinea Hilton - not!

Living conditions in New Guinea were poor by air base standards (though probably better than conditions for many foot soldiers). Charlie says,"The humidity was terrible - nothing ever got dry there, your clothes were always damp."

They lived in tents, and their camp was on a steep slope that was subject to mudslides. Charlie did a little simple engineering, digging drainage ditches around their tent, and when the torrential afternoon downpours came, many other tents slid down the hill, while Charlie's remained in place. They used crates and metal barrels to build makeshift showers - always a hot shower in that climate!

Food was not bad, Charlie recalls - considering the circumstances, the cooks did OK. There was a regular supply ship, but one month it was sunk by the Japanese. They had rice and cans of WW1 era 'bully beef' - but when they opened the cans, they were nothing but maggots. "We had something red, it might have been catsup - so we had catsup and rice for 17 days. That's when we took up hunting."

Near the camp was a stream where they had heard and seen small wild boars. They rigged up flashlights and Springfield rifles and ambushed the boars one night - they shot maybe two or three of them, and they got some good meals once the cooks figured out how to get rid of the bristles.

Camp fauna also included some very persistent ants - they would climb up the tent ropes and drop down on the cots through holes in the mosquito netting.

You would wake up with all these ants biting you - one guy threw kerosene on his cot to try to kill them, got overexcited and lit it with a match - no injuries, but he burned up his cot!

One good thing was that for some reason, the Japanese did not bomb their base very much - there would be occasional nuisance raids, usually a single bomber at high altitude. They didn't do much damage.

Wewak Bee's Nest

Wewak was one of the Japanese air bases on the north side of New Guinea. "There were always plenty of Jap planes flying out of Wewak," Charlie recalls. The Allies were always concerned about any Japanese ships that might be reinforcing their New Guinea forces, and there were Australian coast watchers who monitored Japanese ships from various hiding places, sometimes assisted by local natives.

Some of these Aussie coast watchers had been plantation managers, and they had radios, which they now used to report on Japanese movements. On January 20, 1943, coast watchers had reported a Japanese naval armada off the coast near Wewak. The 321st got a call to send some B-24's up to Wewak to attempt to locate and bomb these ships, if possible. Charlie's was one of five or six planes assigned to this mission, led by the squadron C.O., Col. Faulkner, and as he recalls, when they reached the north coast near Wewak, the ships had already moved, and they never found them.

Charlie recalls, "we had no sooner started searching the area for the ships when we were jumped by a swarm of bees - a large number of Jap Zeros attacked us."

Charlie recalls that the Zero was an amazingly maneuverable aircraft, and they would often press their attacks very close to the bombers, twisting and turning between the Liberators in formation. One Zero made a very close pass, slowly rolling his wings nearly vertical to pass between Charlie's right wingtip and that of the next bomber in formation.

There was no Allied fighter escort in those days, so it was up to the gunners to defend the bombers, and they did a good job that day. But the Zeros also got many hits on the bombers. At this point, Charlie's B-24 was hit, losing its number 2 engine, which refused to feather. Another bomber took worse damage, with two engines hit - it began to lose altitude and drop out of formation.

Cookie with a Zero over Wewak, illustrated with MicroproseEuropean Air War, flight simulation, with user-modified side art, aircraft, and scenery

Col. Faulkner ordered the formation to follow him down, helping to keep the Zeros off the wounded plane in hopes that he could reach the shore or maybe ditch safely. Charlie also believes they all jettisoned their bombs at this point (another report says that Faulkner dropped his bombs with the bay doors closed, damaging the doors - Charlie doesn't remember this, but there was a lot going on at the time!).

The badly damaged B-24 was lost on this mission, though Charlie does not recall seeing it hit the water. The formation got down as low as 2000 feet, flying east in a running fight with the Zeros. Charlie's B-24 took many hits, and the flight engineer (top turret gunner) had a close call when he ran out of ammo and climbed down to get more - at that moment a Zero hit the top turret, damaging it badly - but the engineer was not hurt.

The nose turret lost hydraulic power. Gunners from all the planes claimed twelve enemy fighters definitely shot down in this engagement, with six more as 'probables', and the Zeros eventually broke off their attack. None of Charlie's crew was wounded. His plane also lost its #3 engine on the flight home, but he was light enough to make it over the mountains and return safely to base on two engines.

Col. Cecil Faulkner and Lt. Charles Cook were each awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for this mission, and several other men received Air Medals. General George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, presented the DFC to Col. Faulkner and to Charlie upon their return to Port Moresby. There is an account of this engagement in Wiley Wood's book, 'Legacy of the 90th' which differs in some details from Charlie's recollection.

Distinguished Flying Cross

In that account, the bomber that was downed was piloted by Lt. Jim McMurria and had been on a scout mission that was not part of the formation that launched from Port Moresby. But Charlie distinctly remembers that the lost bomber was part of his formation (and was probably McMurria, since his bomber was shot down that day, and he and his crew were captured by the Japanese). The accounts are otherwise substantially the same, and in any case, the courage of the men on this mission is the important thing.

Night Raid On Rabaul

Night raids against Rabaul continued to be flown, and one of these in spring of '43 was especially memorable.

The flight from Port Moresby was pretty uneventful, even as they reached the target area and split off into single aircraft at assigned altitudes to make their bomb runs. They were flying with a new type of 1000 pound bomb that night, some type of new air-burst fuse that they had not used before. "There wasn't even that much flak, and I thought maybe we could see what the explosion was like. So we dropped and I immediately went into a steep, diving left bank, to evade any flak and hopefully to see the bomb effects."

At that precise moment, two Japanese search lights happened to converge on them. "There was no instrument panel - I was blinded by those damn searchlights! I said, ‘Brad, take it,' but he said, “I can't see either!"

Charlie recalls, "Fortunately our flight engineer, Smitty, was at his favorite station, right between our seats, and for some reason he hadn't been looking towards the lights. He said, ‘I can see!' so I said ‘Well, tell me how to fly this thing!' - Smitty was already trained, in fact he was a good pilot, so he could read the instruments quite well, and he coached us, reading off airspeeds and telling us how to turn the yoke to come out of that diving turn."

But not before the airplane had gotten WAY too fast - red-lined at maybe 300 mph, they were doing over 400 mph in that dive!

We couldn't pull it out - it took three of us, Brad, Smitty, and me, pulling the yokes as hard as we could, and we finally recovered. As they pulled out of the dive, Charlie heard all kinds of noises, pops and bangs. "I'm thinking, oh my God, they hit us - must have been Jap flak - I called the crew to check in, and they were all OK, and couldn't see any damage."

They flew home without further incident, landed, and taxied to the fuel pit. One of the fuel crew yelled to Charlie, "Hey Lieutenant, what happened to this wing? There are whole rows of rivets popped out of it!" The G forces from the dive recovery had severely overstressed the airframe - any more and the wings may have been ripped off!

Even so, when the C.O. asked for a volunteer crew to fly it to Brisbane for repair, Charlie and crew volunteered, and got a one-day R and R (Rest and Recreation) for their trouble. "We figured it had made it back from Rabaul, it was probably good for a few more hours," Charlie says. Cookie was eventually repaired and returned to service after Charlie had returned to the U.S.

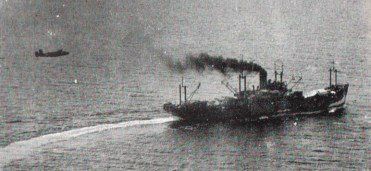

Battle of the Bismarck Sea

Charlie Cook and his crew flew a lot of missions in the Southwest Pacific - he doesn't recall exactly how many, though he guesses perhaps thirty or more. In addition to the many raids on Japanese bases, there were also cases of attacking 'targets of opportunity', as when a Japanese ship was spotted on a patrol.

Battle of the Bismarck Sea

He also participated in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943 - this was the first anti-ship battle that was fought and won completely by land-based aircraft , including B-17's and B-24's from the Fifth Air Force, but also by USAAF and RAAF fighters and light bombers. It was a decisive victory that stopped the attempted reinforcement of the Japanese New Guinea bases in preparation for taking Port Moresby and Australia.

Charlie remembers one single-plane mission where they were ordered to attack a number of Japanese landing boats that were already quite close to shore and attempting to land troops. They flew down and dropped their 500 pound bombs on the boats, then made a number of low passes so the gunners could strafe the boats.

Bismarck Sea was also the first time that 'skip bombing' had been used in the Pacific, and this was said to have been invented by Gen. George Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, though Charlie doesn't recall that the B-24's used this bombing technique. It required flying at the target just above water level and was probably used mainly by the B-25 light bombers.

The Bismarck Sea effort was successful in preventing Japanese reinforcement and Allied losses were light. In addition to such 'major' events, there were always patrols to fly and long-range searches for any Japanese shipping in the region. There were not very many aircraft and crews available at the time, so the pace of combat missions was heavy.

PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

There were a couple of brief R and R visits to Australia, including one trip to Sydney (Charlie brought back a B-24 load of beer and liquor to Port Moresby - the men were quite grateful!).

At this point in the war, there was a shortage of pilots and crews, and there was no rotation policy in place - crews just kept flying indefinitely. The strain of the missions was hard on Charlie as it was on many pilots and crew, and in May 1943, he and several other pilots of the 321st were diagnosed with 'severe combat fatigue' and ordered Back to the States, along with their crews.

This is now known as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder, and is common in military people exposed to combat conditions over weeks or months at a time. Charlie recovered well enough to continue flying in training and transport.

For the remainder of 1943, Charlie was an instructor pilot in the B-24, in Idaho and other locations, though he also got some leave time in the summer of 1943, during which he returned to New England to marry his fiancée, Roberta Patten.

In 1944, he joined the Air Transport Command, and he ferried B-24's and various other aircraft all over the USA and to and from England and Australia. He did not receive another combat assignment. During this time, the after-effects of combat became worse, and though he continued flying, he suffered from a variety of symptoms of stress, including poor sleep and various physical ailments. When he reported these problems to the flight surgeons, they did the only thing they could do at the time - ground him from flying.

Last Duties

The Air Force tried to find a non-flying assignment that would make good use of Charlie's combat experience. In December 1944, he was assigned to a B-24 training base at Tonopah, Nevada, as the ground training director. There he employed a grounded B-24 as a crew combat- and emergency-procedures trainer, something that was quite innovative at the time.

He was a captain at this time, and there was a major who was in a junior position in the same organization and who complained about this. Though Charlie was doing a great job, military thinking prevailed, and he was offered 'any other job he wanted.' He chose an Air Transport Command job, was returned to flight status, and got checked out in the C-54 transport aircraft (military DC-4).

He continued to fly transport and ferry missions through 1944 and 1945. In the summer of 1945, Charlie got verbal orders to go to England to pick up a repaired B-24 and several VIP's for return to the States.

After eleven days of attempts to start the engines, the B-24 in question was finally really fixed, and he flew it Back to Westover AFB, Massachusetts. He was then told to go to San Francisco to join an Air Evacuation Group. But a 'SNAFU' with his personnel files resulted in several months in California with no orders - Charlie just waited for months, checking every day for new orders. Finally he decided that this was crazy - the war was over, and he had enough service 'points' to get out. So he left active duty service in October of 1945.

Post-War life

Charlie returned to New England and continued his education with a masters degree in psychology from Clark University, in Worcester, MA. He worked in a number of positions as a professional psychologist from 1947 on.

Although successful in his career and family life, the stress symptoms of PTSD continued to plague him for many years. In 1966, Charlie was consulting for a psychology research institute in Towanda, Pennsylvania, requiring frequent trips from his home in Keene, NH. It was a very long drive, so the institute started to charter flights for him (airline service was not a convenient option for these locations at the time). A mechanic friend told him about a Piper Cherokee that was up for sale by a flight school in Worcester, MA (it had been used mainly as an instrument trainer, so it was fairly well equipped with avionics). Charlie checked out the aircraft and liked it.

Charlie and Roberta pose with the Cherokee 140 he flew in 1966-71.

He and the institute agreed on a plan to acquire the aircraft, saving a lot of time and travel expenses compared to driving or chartering planes.

Although it had been over twenty years since he had flown an aircraft himself, Charlie found that it came Back to him quite easily after just a couple of refresher lessons and a check ride. Although he never got a civilian instrument rating, his military instrument experience served him well when he encountered the occasional unexpected weather (though he was always a careful flyer and never intentionally flew below VFR minimums).

Charlie had the Piper for about four years and really enjoyed flying himself around for business and for the occasional recreational flight. He hasn't flown an airplane in many years now, and has no desire to do so. He enjoys his retirement, and his garden, securely anchored to the ground. He still dispenses flying advice now and then, which as a student pilot, I always appreciate!

Conclusions

Charlie always was interested in airplanes, and he was happy he got a chance to fly as much as he did. Like many 'citizen soldiers' in WWII, he did not much like the military life, with its regimentation and red tape, but he recognized there was a job that needed doing, and he did not hesitate to sign up and do that job.

Charlie with a B-24 that visited Keene, NH in 1996.

Though only 22 years old himself, he felt a powerful responsibility for the lives of his even younger crew, who depended on him to fly them safely through all the dangers the skies and the Japanese could throw at them.

It was a terrible and wonderful job all at the same time. He did the job, took care of his crew, and suffered badly from the stress, but never asked for any special thanks or credit.

We owe a lot to Charlie and the people like him who did so much at such a young age during World War II - we live in freedom and prosperity today thanks largely to the work of men like him. I want him to know that I and many others are very grateful for his service and for his sacrifices.

Copyright 2000 by Bruce Irving

Microprose's 1998 flight sim European Air War flight sim was used to illustrate 'Cookie' in action (note that you can't fly the B-24 in this sim, but you can set up fighter escort missions with bombers). European Air War is a great flight sim, and there are many free add-ons created by users to enhance it. I used Pacific terrain files and a Japanese Zero model, and I modified the side art to create 'Cookie' and 'Big Chief' from the 90th BG. I found these and various European Air War utilities on Cord's EAW Page, an excellent site.

References

The Jolly Rogers : The Best Damn Heavy Bomber Unit in the World : Southwest Pacific 1942-1944

(Schiffer Military History Book) by Jules F. Segal (Editor)

This book is a reprint of a book originally published in 1944. It has a lot of photographs, cartoons, and stories, with a great period feel - it almost seems like a high school yearbook for the 90th Bomb Group. It includes the color version of the side art from 'Cookie' along with a brief description of the night mission over Rabaul described in this article. It also mentions another incident in which Cookie flew on instruments for 9 hours at water level through a storm, and also shot down seven Zeros. Charlie doesn't remember this particular incident - they were often flying on instruments, but it's also possible that another crew was flying Cookie on this mission.

This book is available from amazon.com.

Legacy of the 90th Bombardment Group : 'the Jolly Rogers' by Wiley O. Woods (1997)

Legacy of the 90th Bombardment Group : 'the Jolly Rogers' by Wiley O. Woods (1997)

It covers the history of the 90th from the early part of the war (pre-Jolly Rogers) until the end. Mr. Woods was a member of the 90th BG and provided useful background information for this article. Thanks, Wiley!

The Jolly Rogers: History of the 90th Bomb Group During WW II By John S. Alcorn

This book is out of print, but Jason Dilworth (email Bigchiefcrew@cs.com) was kind enough to provide me a scan of 'Cookie' in flight from this book. Thanks Jason!

Bombs Away! (author and date unknown)

This was a book that was specific to the 321st Bomb Squadron, perhaps printed by the Army or privately published. Jason Dilworth received a copy from the pilot of his grandfather's B-24 and was kind enough to scan and send me the crew picture that appears in this article.